After running out of things to do in Bishkek, we traveled to Min Kush. In olden days, Min Kush, Kyrgyzstan was an industrious Soviet manufacturing hub, and a leading producer of uranium. These days, the town has all but died, and is filled with abandoned factories and crumbling mansions. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t warm hearts to be found.

We’ve ridden in minibuses with windshields too cracked to see through. Taxis so decrepit we watched the road whiz by through holes beneath our feet. Buses incapable of driving faster than 20 kilometers an hour.

But this rickety Volkswagen van hurtling towards Min Kush, Kyrgyzstan takes the prize for most dilapidated vehicle to date.

Every few minutes, the van lurches with a mechanical growl, and the driver, a tiny old Kyrgyz man, wrestles violently with the gearshift. He smashes it every which way, using brute force to get the stubborn vehicle to shift. At times he’s victorious; at others, the van wins, throwing its inhabitants forward as it screeches to a halt. All able bodies then clamber out and push the van until the engine roars to a start once more.

Occasionally we run to the nearest stream with plastic soda bottles to fetch water for the smoking engine.

It’s a dubious form of transport to be sure, but this is the only we can get to Min Kush, a tiny town in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan.

To the middle of nowhere we go

Min Kush isn’t exactly one of the main tourist attractions in Kyrgyzstan. So after hours of resistance, the pilot steers his craft down the final stretch of unpaved road into town.

And what a grand road it is: flanked by lush green trees, golden rays of sunlight trickle through their leaves and illuminate its rocky path. Perfectly pointed mountains rise up in the distance, some covered with pines and grassy meadows, while others are barren, red rock spires.

As we roll into town, there are no HOTEL or ГОСТИНИЦА signs. The lane is lined by curiously grand but peeling Soviet houses, juxtaposed with fences made from mismatched pieces of wood and scrap metal.

The woman sitting in front of me turns around as we rumble up the main road.

“Do you have an address in Min Kush? Where will you sleep?” she asks in Russian.

With a rueful grin, I shrug. “We have a tent?”

She clicks disapprovingly, exchanging a few words with the driver before turning back ‘round to look at me. “It is too cold, you will freeze. Stay in our home instead.”

A warm room and hot food instead of a cold tent and bread for dinner? Well, if you insist.

The view from our hosts’ home wasn’t too shabby!

A family reunion

It turns out the woman is returning from Russia for a family reunion, and the van’s pilot is her father. Over the course of the evening we’re introduced to the rest of her family: her mother, retired, her two sisters, all of whom left Min Kush to find work, and their million and one children, all wide-eyed as they examine the foreign aliens. No one speaks English—it’s a Russian-only night.

The father, also a school teacher, takes a warming to me after I attempt to act out the phrase “World Nomad Games” when my vocabulary fails. Miming horse riding and archery didn’t cut it, but it did earn hearty laughs. His wife is initially cold after I mistakenly asked if she was his “woman” instead of his “wife”, but eventually she accepts my linguistic blunder.

Late in the evening, one of the sisters is showing me how to grind tomatoes for sauce, and I ask her about Min Kush’s residents.

“I left to find work. So did my sisters. There is no work in Min Kush,” she says as she pokes at a tomato in the grinder, “… most people have left.” Her brow furrows as she says it, and I don’t probe further.

No need, history reveals itself the next day.

Sunset over Min Kush

From riches to rags

Armed with water and freshly baked bread from the family’s oven, Sebastiaan and I set off to explore the region. After mere minutes loping down a dusty path, a wizened old man in a tattered hat appears next to us. The usual questions are exchanged in Russian as we walk:

“Where are you from?” America and Holland.

“You speak Russian?” Yes, a little bit. But very badly.

“Good! Where are you going?” Just… around. In the mountains.

“Ah, there are mountains everywhere. But here, look at that! More interesting.” He points to some crumbling old buildings to the side of the road. Their unremarkable exteriors had escaped my notice before, so I peer at them more closely.

“They were factories, from Soviet times,” he gestures, nostalgia shining in his eyes. “When Soviets were here, there was much work! Many, many, people in Min Kush. More than 20,000 people!” He points at himself proudly. “I worked in the factory. We made everything. I had lots of money. Everyone had lots of money.” Ah, so that’s why all of the houses in town are so large and grand.

Then the light in his eyes fades, and his shoulders slouch with the weight of bygone days. “But then, when Soviets left, the factories closed. Finished. Now, there is no work, no money. Life was good with Soviets, but now I have no money.”

My Russian is not good enough to respond, not that I know what to say if I could. Instead, we walk on past the factories in silence for a time, before he sticks out his hand hopefully. “Give me money?”

His story is sad, but we refuse. He’s not particularly offended, and after silently following us for another few minutes, he stops and sits at the side of a stream, waving goodbye.

In the shadows of the Soviets

The day is spent trooping through tiny villages, hiking through foothills, and stopping for chai in locals’ homes. We’re weary by the time we turn back to Min Kush, but we can’t resist poking around in the abandoned factories.

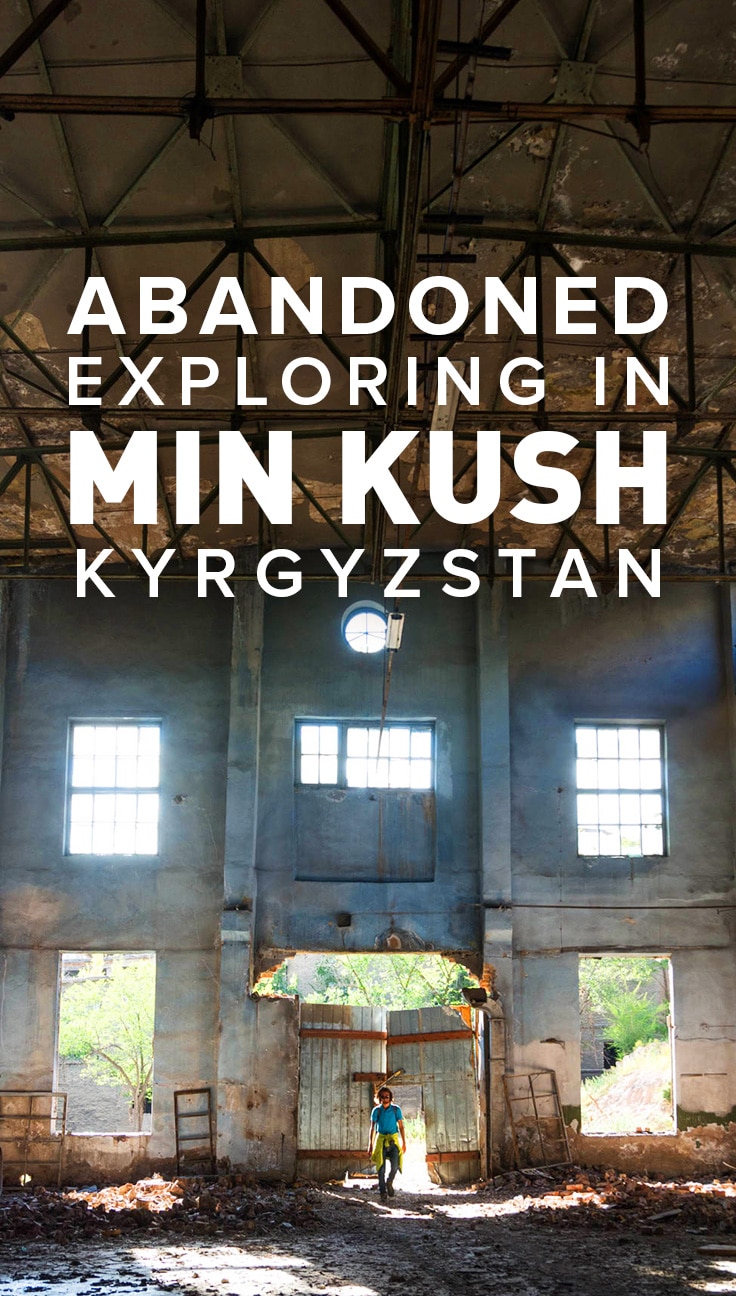

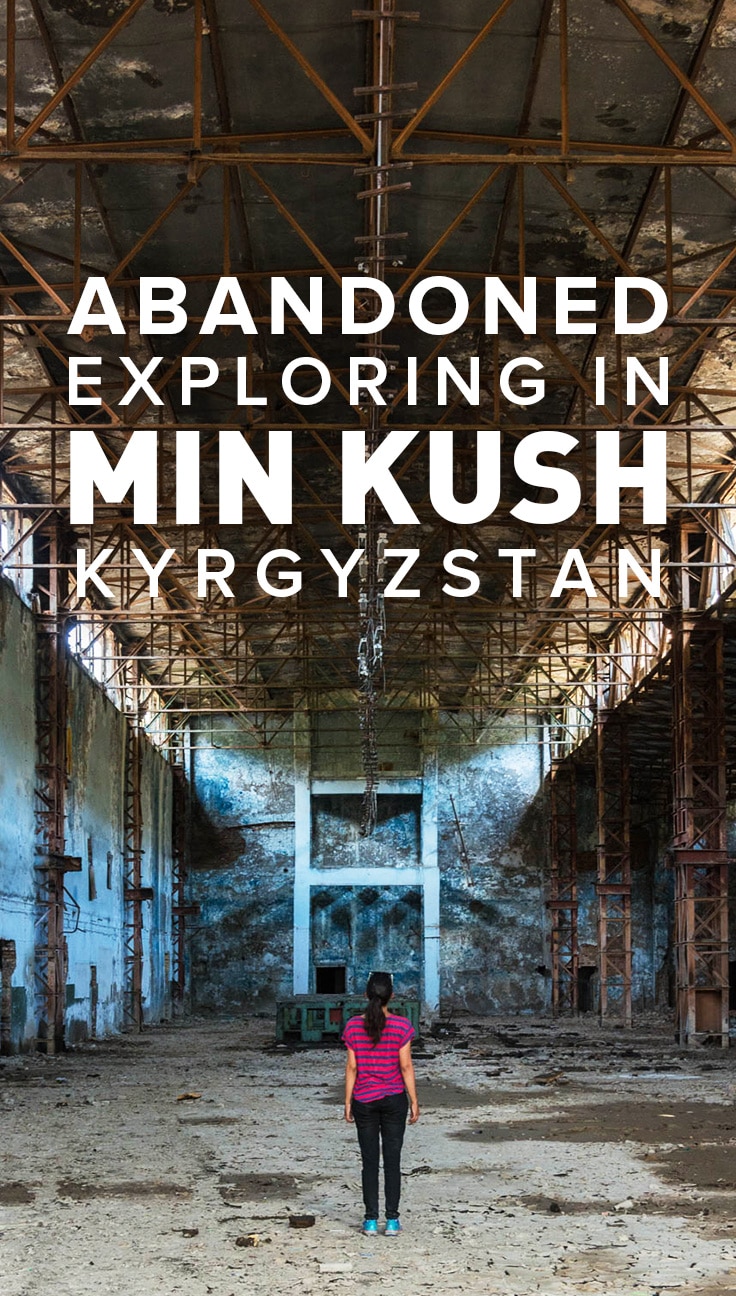

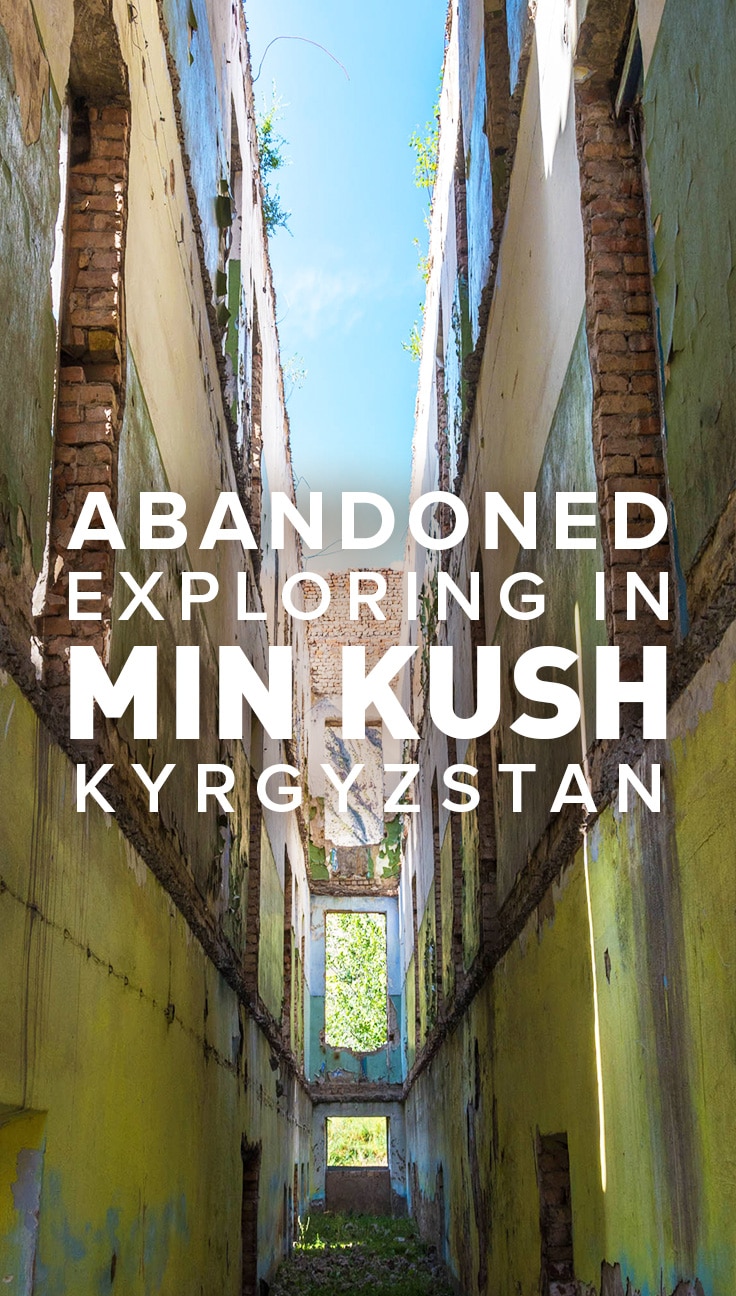

Almost a dozen buildings—and remnants of— are sprawled at the foot of a mountain. Weeds poke through every available crevice, while a rogue group of donkeys step gingerly through the rubble in search of grass. Some of the buildings look like they’ve been purposefully destroyed, while others are eerily abandoned, as though all of their occupants simply disappeared at once.

Bizarre machines fill some of the gaping concrete halls.

Others have been stripped, devoid of inhabitants aside from some old pens and mud riddled with donkey prints.

The emptiness adds to the sense of scale; it’s easy to imagine thousands of workers toiling away in these halls.

Watch out for ghosts…

The factories produced a variety of goods, but Min Kush was most valued for being one of the Soviets’ largest uranium supplies. The health risks of mining and processing uranium were known at the time, but miners were paid well enough to ignore the high cancer rates. We learned about this radioactive bit of history later on, so here’s to hoping we didn’t inhale too much of the factories’ history.

Lungs sufficiently filled with asbestos, dust, and potentially radioactive remnants, we climb through broken windows into the world of light and begin our walk back to Min Kush. On the way, we discuss our newfound appreciation for the town: from industrious wealth to crippling poverty, it’s an example of the price many paid for Kyrgyzstan’s independence from the Soviets. As with much of Central Asia, it makes one wonder if the benefits of Soviet occupation outweighed the detriments after all.

Regardless of the answer, life must go on. Safe from the bitter cold outside, we sit around the dinner table with our hosts later that evening, sharing plates of homemade manty, dumplings. The sisters laugh and make jokes with the children, while their father, bones creaking with the weariness of age, sits to the side and smiles.

They’ve gone from plenty to poverty, yet they didn’t hesitate to open their doors to strangers. Once again, we find that those with the least to offer are the ones that give the most.

The father and his grandson

How to get to Min Kush, Kyrgyzstan

There’s one marshrutka from Bishkek’s western bus terminal to Min Kush each day, departing at 6:50 in the morning. A ticket is 350 som.

As usual, we learned this at 7:00, and had to find a different method of transport; we took one of the many marshrutkas to Chaek, and got a ride from there. A marshrutka to Chaek is 300 som, and the ride is about 5 hours.

We recommend staying at Apple Hostel in Bishkek, as it’s right next to the bus station (no need to worry about missing the marshrutka) and the staff are awesome. Aigul, the manager, was the one that suggested Min Kush to us.

Planning a trip to Kyrgyzstan? Don’t miss our budget report for backpacking in Kyrgyzstan!

Yo guys. Been reading your blog on Kyrgyzstan. Looks amazing. Me and a mate are actually travelling there in a couple of months and we want to travel by horse ideally. Do you guys know if we could simply hire a horse each and a guide from a market or something in kochkor? Don’t really want to go through an agency or tour company. Do you reckon it’s possible to just wing it like this? Would appreciate any advice or info you’ve got. Thanks in advance and keep up the good work. Travel safe. Xx

It helps if you have some Russian skills, but it’s definitely possible to hire a guide and get a horse ‘on the street’, so to speak. There are usually guys hanging around in popular hiking/horse riding towns to whom you can talk, but as far as we know there aren’t any designated places. Ask around before you go, as plenty of others are into this kind of thing, too. Some people will try to steer you to a tour agency anyway (this is where Russian comes into play), but if you’re adamant enough, it should definitely be possible to do it without booking things through an expensive agency.

You guys are from the US and Netherlands which comes under top 20 richest countries in GDP per capita on the other hand Kyrgyzstan is ranked among the top 30 poorest countries in the world per capita. If that guy had asked you for some money you should have given it to him. €1, $1 or £1 wouldn’t have made you poor. No one in the west usually offers accommodation and food to complete strangers and meanwhile you reciprocated the hospitality shown by the locals by refusing to give them money. No matter how much you say that you are the citizen of the world its not going to change the fact that you are an American who just knows how to take but has never learn’t to give back. Happy Travels.

You do know that giving to beggars usually does more harm than good, right? It perpetuates the idea that people are dependent on others, and does nothing to improve the lot of the person receiving the money in the grand scheme of things. Giving money to people simply because they ask you when you walk by is rewarding them for bad behavior. We left a suitable amount of money with the people hosting us, as well as a thank you card drawn by Alex. But the fact that we’re better off than other people doesn’t mean we should just start handing out money left and right to people asking for it. That just perpetuates the problem.

Super interesting post! It is so important to see places like this in countries like Kyrgyzstan as it really humanizes the history of the place… and what is going on in certain regions even here today.

Agreed. We hardly knew anything about the region before we came (aside from some vague references to the Great Games). Hopefully more people will come and realize not all countries ending with ‘stan’ are dangerous and scary.

Wow, this is so cool! Very entertaining story about how you got there and the family taking you in and with some great pictures. Interesting piece of history as well! Do you know by any chance if there are more villages like that, where the soviet union brought lots of work of which the remains are still seen in the form of old factories etc?

Glad you liked the story. Honestly, we’re not sure. Check out the forum of https://caravanistan.com/. There might be people who know more.

Cool, thanks for the tip!

This place looks AMAZING. Thank you for sharing this with us. Adding this to my list.

“Soviet occupation”? After joining the Union, Kyrgyzstan saw considerable cultural, educational, and social change. Economic and social development also was notable. Literacy increased, and a standard literary language was introduced. Modern medicine was introduced, along with vaccination and education. Jobs were created, and women were liberated…

Tsk-tsk-tsk… for supposedly well-travelled people, you spit out an awful lot of second-hand brainwashed propaganda.

Oh, and Om Prakash Chautala above is right. Your response to him about “rewarding bad behavior” makes no sense. You just described those people as being decent folks who were down on their luck. What “bad behavior”? Getting rid of the “soviet occupation”?