Our first time celebrating Eid al-Adha in Lahore, Pakistan, and seeing animal sacrifice in action. See the end of the post for tips on traveling in Pakistan during Eid al-Adha.

Warning: Graphic images ahead. If photos of dead critters (cows in particular) and/or blood and/or guts makes you squeamish, you should probably go read something else.

The cow’s doleful brown eyes stared at me before returning to the ground. Cows rarely seem particularly cognizant, but this one, looking defeated in its tired circus outfit, seemed to realize nothing good was coming in its near future.

The blood on the ground was probably a good hint.

It knows.

The cow’s doom was imminent; it was the first day of Eid al-Adha, the holier of Islam’s two annual Eid holidays. During the three days of Eid al-Adha, countless goats, cows, sheep, and camels are sacrificed all across the streets of Pakistan and the Muslim world. The sacrifices, called qurbani in Pakistan, are made in honor of Abraham’s (Ibrahim) willingness to sacrifice his own son, Isaac (Ishmael), at God’s command. Yes, basically the same story you’ll find in the Bible or Torah.

After slaughtering the animal(s), one third of the sacrificial meat is given to the owner’s extended family, and one third is distributed to the poor. Though charitable, it sounded like a bloodbath, and in practice… well, it was, in Lahore at least. But the atmosphere in the days leading up to Eid was undoubtedly festive, and we couldn’t help but get caught up in it all.

Sitting, waiting, eating.

Goats on demand

The first signs of the approaching Eid came several evenings before my bovinian encounter, as Sebastiaan and I stood on the streets of Lahore with our friend Waqas. They waited as I ordered a car through Careem, an Uber variant popular in Pakistan. I flicked through the different car options—Go, Go+, Business—and noticed another icon amongst the list, a goofy goat face labeled “Bakra”.

Entertaining dreams of riding through the streets of Lahore in a goat-drawn chariot, I tapped the icon several times to no avail—I could only schedule future rides. Goats galloping through Lahore’s walled city would have to wait until another day. Thwarted, I turned to ask Waqas about the icon.

“Bakra means goat. You can order a bakra goat for Eid sacrifice through the app, and they’ll deliver it to your house whenever you want,” he answered nonchalantly, scrolling on his phone as our car pulled up to the curb. Clearly he did not find the concept of goats on demand as wondrous as I.

As our Careem navigated through Lahore’s incessant traffic, more signs of the coming holiday flitted before my eyes. Flapping plastic banners advertised cheap cows and goats for sale, priced by weight. Makeshift roadside animal markets filled with men surrounded by bug-eyed goats and sheep lined the streets. Young boys led defeated animals in colorful garb down the city’s boulevards. Impossibly pale Pakistani ladies in glittering kurtas stared down at me from billboards, a reminder that buying new Eid clothes is equally as important as buying an animal for sacrifice in our capitalist world.

Lahore was ready for Eid.

Casually strolling with cow down Mall Road

That’s one way to get your camels home…

Last minute shopping trip?

Questing for qurbani

On the first day of Eid, Sebastiaan, Waqas, and I headed to Lahore’s Walled City on a quest: to see a qurbani, sacrifice, in action.

Back in the days of the Mughals, before overpopulation and city sprawl, a defensive wall surrounded the grand city of Lahore. In the current era, Lahore has metastasized and modernized far beyond the boundaries of what’s now known as the Walled City, but life still goes on within its ancient walls. The old city of today is an endless maze of narrow alleys stricken by tangled cables and peeling haveli mansions well past their glory days, and this is where we began our quest.

On most days, the old city is abuzz with shopkeepers, pedestrians, motorbikes, and loitering folk. On the first day of Eid, however, it was deadly silent. We wandered aimlessly through the post-apocalyptic world as we hunted for signs of a sacrifice to be. Initially, all we found were grisly remnants of blood and piles of animal hides crawling with flies.

Whoops, someone forgot their heads here!

Hides piled up for donation

We dove deeper into the labyrinth, and eventually found ourselves on a street filled with goats and cows tied to the walls, munching on last meals of fodder and grains.

Circus cow does not seem too happy about its fate…

The alley opened up into a courtyard, where a local family invited us to sit and have a drink; they would be sacrificing a cow in a few minutes they said, and we were welcome to watch. A henna-painted goat decorated the courtyard with droppings for a few minutes while I sipped my Sprite, eventually interrupted by men leading a big brown cow with a shell necklace through the courtyard into someone’s home.

Showtime.

Cow down

Young boys followed the men into the room, armed with mobile phones and cameras to record the macabre proceeding. A young man appeared with more soda for Sebastiaan, Waqas, and me, should we get thirsty for something other than blood during the sacrifice. I stepped gingerly around a severed, skinned cow head on the floor, and settled just out of reach of kicks and blood splatters.

This was the first time I’d actually watched an animal die; I was afraid I’d find the sacrifice sickening, but the worst part wasn’t the blood or decapitation—it was seeing how completely clueless the cow was of its impending death.

The cow stared blankly into space until several of the men stepped forward and wrestled it to the ground. Even then, it only weakly struggled as more men stepped forward to lash its legs together with rope.

Down it goes

A man in a bloodstained white salwar kameez stepped forward, clutching a sharpened butcher’s knife. He murmured a prayer before sawing into the cow’s throat. Blood sprayed from its half-severed head, more vividly red than I could ever imagine. Some of the boys moved closer, fascinated, while others recoiled in horror. The cow’s body continued to twitch and limply flail even after its’ eyes clouded over.

Goodbye, cow

With a final flick of the knife, the man cut off the cow’s soiled necklace, and the others got to work hosing the blood off the body and the floor. Once somewhat clean, they again clustered around the body, and deftly began skinning it.

Piece of meat pie cake

Satisfied (if that’s the right word) with our first sacrifice, Sebastiaan, Waqas, and I stepped out for some fresh air, and began wandering Lahore’s bloodstained streets once more.

Eid al-Adha in Lahore’s old city

This sheep knew what was coming.

Many sacrifices were done right on the streets.

… and were left until later.

There’s no place (to skin critters) like home!

Things did get quite grisly at points.

You have to wonder if sweeping really serves a purpose here…

Watching the zoo from the comfort of a local family’s haveli

Street kids caught in the act of camel taunting

Beef, anyone?

Lonely last moments.

Sacrificial crescendo

Our qurbani quest came to a climax on the second night of Eid al-Adha.

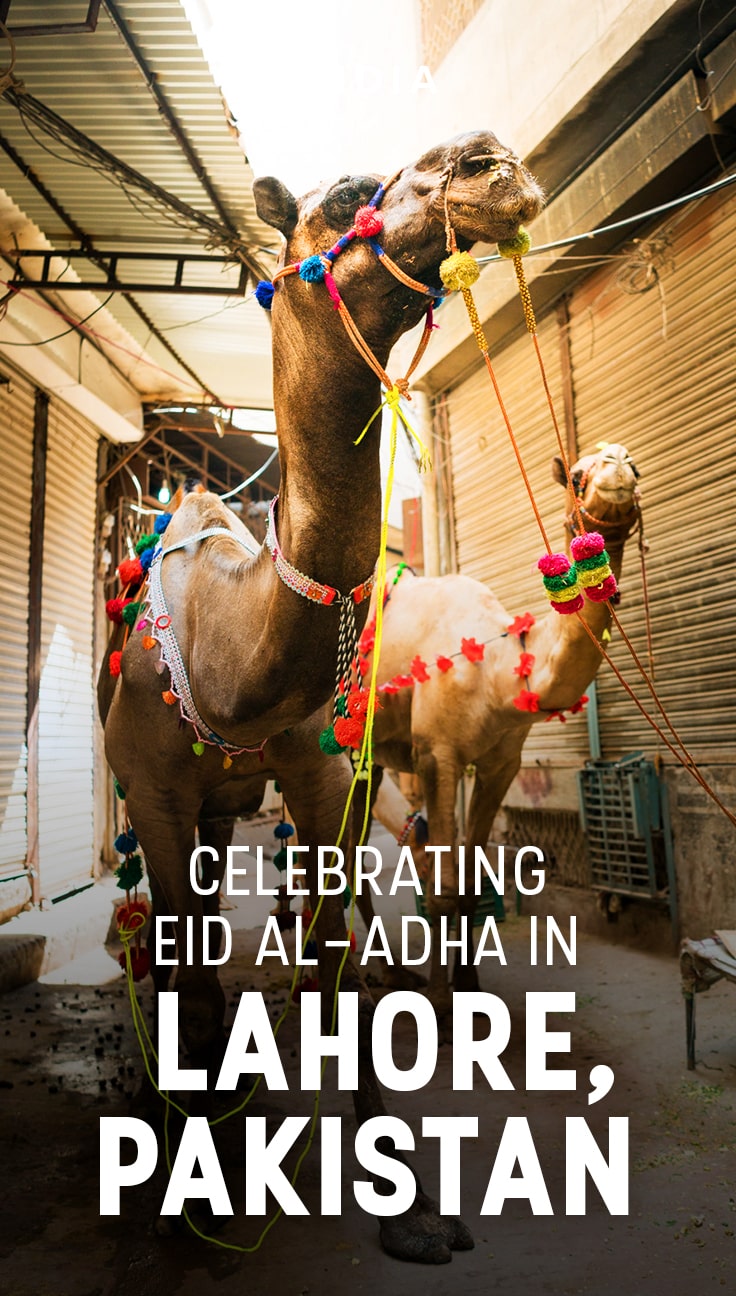

During our earlier wanderings, we learned of a man who purchased not one, not two, but six camels for sacrifice. The massive camels, decked out in fluffy fluorescent pompoms and beads, were hard to miss on the old city streets. We came to examine them several times, and eventually ran into some neighborhood boys with more intel. They told us to come back a bit before midnight on the second night of Eid if we wanted to see them slaughtered.

Camels awaiting their demise

A six camel sacrifice was a spectacle we couldn’t resist, and so, at midnight the next day, we found ourselves in Lahore’s Walled City once more.

We weren’t the only ones. The alley was packed with eager boys and men, and one camel carcass already decorated the blood red street. The sea of men parted for an instant, and thanks to Sebastiaan’s foreign looks and my being the only female present, we three qurbani questers were ushered atop steps right at the foot of the dead camel.

The eager crowd

Another camel was led into the crowd right after us, and unlike the cow earlier, this animal was most definitely cognizant. It strained and pulled at its lead as men hooted and phone cameras flashed.

What a way to go, eh?

A hired butcher approached to slice its throat, and the camel’s legs began to flail and kick. The crowd scattered, savvy to the damage a distressed camel could do.

Finally, the butcher regained control of the camel, wrestled it to the ground, and sliced its throat. The act couldn’t have been more theatrical: two bright streams shot out from its neck, causing the men to retreat once more. Frothy red blood quickly filled the ground, as though someone had spilled a beet red lassi all over the floor.

The end

As the spectacle slowed to a slow trickle, the crowd dispersed—sort of—and skinners moved in to slice and dice camels #1 and #2.

Nothing like a good camel skinning to entertain your young boys on a Saturday night!

Which bit would you choose for your barbecue?

Old city dons

As the bloodthirsty crowd waited for the bloodbath to continue with camels #3 and #4, the camels’ owner invited us out of the sweaty mosh pit and into his nearby home for a moment of fan-cooled bliss.

In the stark black and white entry room, the man, also named Waqas, towered where he stood. A rogue lock of hair fell casually across his forehead, and a thick mustache occupied his upper lip. His blue plaid shirt remained unbuttoned at the collar, showing a hairy chest and a solid gold necklace. A lone photo of him surrounded by other macho men adorned with gold necklaces was the only decoration on the walls. I couldn’t help but think the men looked like mafia, but I shook the thought out of my head.

Several other boys entered the room—Waqas’ family—and we all got talking. He eventually brought out his phone and pulled up a photo. It was of one of the men from the photo on the wall, wearing a crisp white salwar kameez and three massive gold chains around his neck.

“He was a good don,” Waqas said with a grin, “A good don must have long hair, wear salwar kameez, and wear lots of gold.” He shook the phone for emphasis, and I peered at the photo once more. Yep, this guy fit all the criteria for a mafia don. Waqas continued on, “When he came to the Walled City, he would come with 100 men for security.” Security from what?

We all kept on talking, taking the occasional break to observe the chaos outside.

Camel #3

As more camels met their ends, more and more hints emerged to convince us the men were mafia.

Someone mentioned the camels for slaughter outside cost two lakh rupees (200,000 Rs) each… that’s $12,000 worth of camels in total. Mafia Waqas was quick to clarify that those weren’t the only animals his family was sacrificing for Eid—he had several goats as well. He gave us his business card at one point, which claimed he was but a fabric salesman. Hm.

During a break in conversation, we stepped outside to observe the hired butchers chopping up the camel meat into steaks. A potbellied older man in a white tank top sprawled on a chair, watching over the process. Mafia Waqas introduced him as his father in law, once “chairman” of the Walled City bazaar… whatever that may mean in practice. Another potbellied, mustachioed man came over to join us—Mafia Waqas’ uncle, current chairman of the bazaar.

Lahore’s temporary meatpackers district. It’s best not to dwell on the hygiene standards.

A few minutes later, Mafia Waqas pulled up another photo on his phone. This time, instead of a man in a white salwar kameez, it was a blurry shot of a caged white lion. He proudly proclaimed the lion was living in his country house. When we eagerly asked to see it, his eyes narrowed, looking suddenly shifty. “Um… visiting it would be very… difficult.”

As the night grew darker, the mafia dons and dons-to-be filled our ears with warnings about the dangers potentially waiting for us on the old city streets outside, and it was starting to get to us. Sebastiaan, Not-Mafia Waqas, and I said our goodbyes, stepped back into the camel crowd outside, and made to leave. As we began to move away, Mafia Waqas ran out and stopped us.

“Please! You must take some meat with you. I insist.”

We all exchange glances and grins. Not going to say no to a free bag of camel meat now, are we boys?

A quick sojourn into the upper areas of Mafia Waqas’ home resulted in a fat blue plastic bag of camel meat clutched in Sebastiaan’s hand. A flurry of Eid Mubaraks were exchanged with the mafia don and clan, and we returned once more to the darkened streets of the old city, several kilos of camel meat in tow for a barbecue the next day.

All in all, not bad for our first Eid al-Adha.

At least the boys were having fun!

Tips for traveling in Pakistan during Eid al-Adha

Traveling during Eid al-Adha can be a bit tricky, as transport schedules are disrupted and many businesses are closed before, during, and after the holiday. Rather than fight the disruption, why not take a few extra days to experience Eid?

Logistics and traveling during Eid

- Eid al-Adha is officially three days long. Use Google to find out when the next Eid al-Adha is.

- Most businesses will be closed on the first and second days.

- Restaurants and some small food stalls will be open on all days.

- Official offices close for the three days, and some are not operational on the days before and after.

- Daewoo bus services are disrupted during the holiday. In 2017, only advance tickets were sold for the days before Eid, the second and third day, and the three days after. Tickets were to be purchased at most four days in advance. No buses ran on the first day of Eid.

- Private car hire is your best bet if you want to travel long distances during the holiday.

- Careem and Uber do still run in the cities during Eid.

Joining in Eid celebrations and traditions

- Wander around in the days before, and you’re sure to see some animal markets on the streets.

- If you’re in Lahore, the Walled City is a good place to see some qurbani in action. Morning is best. Don’t be afraid to ask around to see who’s doing what, and follow the animals.

- Don’t wear nice shoes—or white shoes—in the Walled City. It’s gonna get bloody.

- People generally barbecue their meat on the second and third days of Eid. If you want to find a local to join in the celebrations with, check out the Facebook groups Backpacking Pakistan and The Karakoram Club.

I was wondering why there’s no article about Pakistan after your return and then here it is. Always a delight to read your articles. Thumbs up.

Haha we’re always super behind on our articles. Glad you liked this one, though 🙂

A great article, but given the preconceived notions people across the globe have about Pakistan, bloody pictures of Eid-ul-Azhaa, maybe not the best idea. Its all true what you have described and im glad you have given it a bit of context but could talk about plenty of other festivals and events.

Nevertheless, keep up the good work, keep travelling.

We write about what we find interesting, and this was super interesting to us. Eid is also celebrated all over the world, even in many non-Muslim countries, as Muslims live everywhere. We don’t think this will do anything to affect Pakistan’s reputation.

Of all of the wonderful and beautiful things in Lahore, this was the best you could come up with? A very negative portrayal.

And how exactly is this a negative portrayal?

Showing Qurbani of one animal would have served the purpose but to devote the whole piece only to the dressing-up and dismemberment of different beasts and not highlight the other important activities that make this occasion except to just mention them in passing seems a bit excessive. I was born in the faith and know what this festival comprises. Unfortunately you chose to highlight only the grisly aspect. You know I am your fan and soak up all your travel stories but this time I am left with a unsettling feelings and its isn’t due to gruesome pics alone. And though you may not have done anything to “affect” Pakistan’s current reputation for better or worse, but unwittingly (and I hope that it is so) you may have reinforced it. Don’t underestimate the power of subliminal persuasion.

Like I said before, we write about we find interesting, and to us, this is interesting (we admit, we are morbid people). The reason we don’t have photos of any other aspects of the holiday is because we didn’t experience any other celebrations firsthand. We don’t get to see the more intimate or private aspects of the festival, and we can’t just walk into mosques and start snapping photos of people praying. This is what we see, so this is what we show others. We like to show all kinds of aspects of the countries we visit, not just rainbows and flowers.

You’re essentially asking us to censor ourselves because we’re showing people something that might negatively affect or reinforce your country’s reputation. We understand your concerns, but do realize that does more to affect Pakistan’s reputation of an intolerant country than anything we might write.

What a festival! I’ll never forget my first Eid in Pakistan. Religiously, it’s such a big day. Yeah, it’s grisly, but it’s reality – it happens, and it’s a big deal.

No, your article is not creating a bad impression of Pakistan.

It was super interesting to walk around and see what was going on. Really nice of people to show us, even though we are tourists. And yeah like we said, complaining about this does more to tarnish a reputation than depicting what’s going on.

What you portrayed is what you saw. I have a question which no Muslim has ever been able to answer.

Abraham did not sacrify an animal did he? He offered his son to Allah right or wrong?? If this is the case and if Muslims believe this story, why don’t Muslims offer their sons and daughters to Allah and wait for Allah to save them? Why kill the poor animal who have nothing to do with what Muslims believe??

This is because Muslims have realized that Allah does not exist and hence they must sacrifice the hapless animal and not their own children as no one will save their choldren if they sacrifice their children.

Public display of butchery is a socialogical malady first and a health concern second. Muslims have no option but to continue celebrating this as this shameful show or terrible cruelty to animals and total insensitivity towards enviornment runs economy worth billions of rupees. This loathsome cascade of murders also strengthens another pillar of Islam which is terrorism as skins are donated to militant organizations to kill more human beings. Probably this is the ultimate sacrifice death of a non believer is what Allah loves the most

Adhering to such barbaric traditions without any llgoes on to show the doomed future that lies ahead of Islam and slaves of Allah. ( Muslims are not followers they are slaves of Allah by their own admission)

Thank you for writing this. I see a lot of Islamic YouTubers talking about how qurbani is a beautiful process, designed to give charity to the poor and how in halal sacrifice it’s very important to make sure the animal does not know what’s coming and if it even sees the knife or gets scared, it is spared. Well now we can see how qurbani is actually performed. A festival of cruelty.