Dual pricing in tourism is a common practice all throughout Asia… and it’s utter nonsense. Here’s why dual pricing is unfair, and what governments could do instead.

If you’ve traveled in Asia, you’ve probably encountered—and debated—”dual pricing” before.

For those not in the know, dual pricing is a practice where ticket prices for sights are determined by nationality, with locals paying less than foreigners.

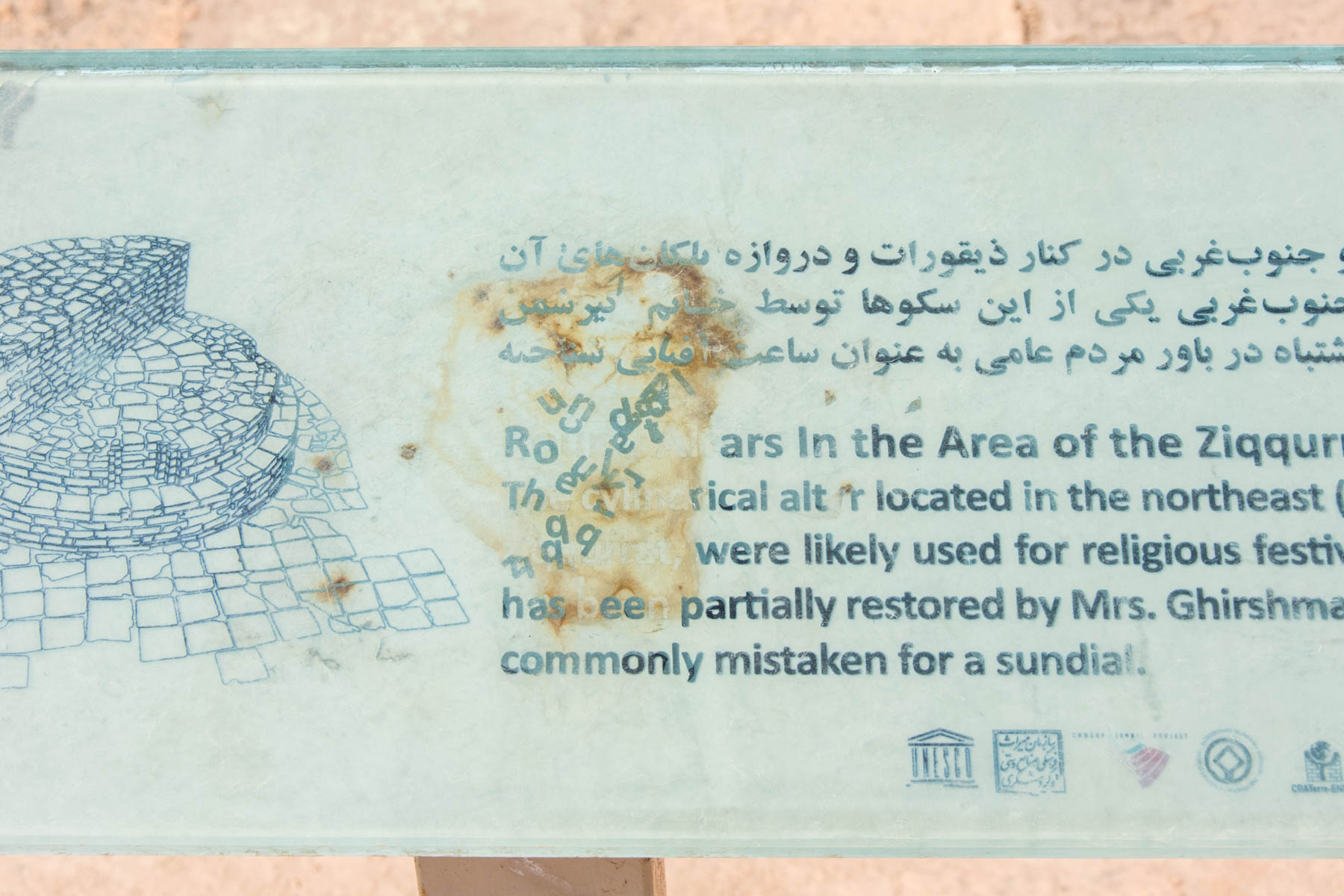

Dual pricing at Vakil Mosque in Shiraz, Iran. Local price: 1,000 rial. Foreigner price: 150,000 rial. Say what?

The extremity of the pricing system varies from country to country. In Iran, we paid 5 to 8 times the local price. In India and Pakistan, foreign tickets are usually 10 to 20 times more expensive than the local variant. And in Thailand, foreigners often pay twice as much as locals. The most extreme example is Petra in Jordan, where foreign tourists pay up to 90 times the local price.

The arguments in favor of dual pricing seem compelling:

- The money is needed for maintenance

- Poor locals shouldn’t be priced out of their country’s sights

- Foreign visitors have more money so they should pay more

- Entry prices in other countries are high, so they should be high everywhere

Many people agree with these… but I’m here to say they’re utter nonsense.

The money is not used for maintenance

It’s not a matter of opinion: maintaining cultural sights is of upmost importance. No one wants to see the world’s heritage fall to ruin.

The problem is that, in countries where dual pricing is common, it’s questionable if the extra income generated is actually used for maintenance.

Maintenance, eh? Trash in Deosai National Park, Pakistan.

Plenty of sights we’ve visited in the last year could really use a scrubbing… at least. Having some trash bins on the vicinity wouldn’t be terrible idea, and some signage in English (or French, or Chinese, or anything but the local language) would go a long way. If foreigners are going to be charged more, there should at least be amenities to justify costs.

Of course, all of this is lacking. This raises the question, what happens with the money?

The other day we shared some uncomfortable findings on our Facebook page about millions of dollars of discrepancy in the Taj Mahal’s reported revenue, versus what it should be calculated from reported visitor numbers. No one was surprised.

Poor management is one of the reasons third world countries are what they are, and corruption plays a huge role. Since there’s hardly any transparency or accountability in these countries, it’s reasonable to assume much of the income generated from tickets ends up in the pockets of officials. Even worse, it might be squandered on ill-advised policies and white elephant projects that don’t benefit the local population nor the country.

Quality upkeep at Choqqa Zanbil in Shush, Iran.

If ticket revenue was visibly used for maintenance and improvements, the argument for dual pricing would be stronger. But, of course, it’s not.

The Bibi Ka Maqbara in Aurangabad, India is 15 Rs for locals to enter. And even that can be too high.

People are always priced out

Perhaps the most compelling—and most fallacious—of the arguments for dual pricing is that locals mustn’t be priced out of visiting sights. Though it’s a nice idea, the reality is, unless entry is free, someone is always priced out.

The population of the countries where these practices are most common are, generally, poor. Many people struggle to get food on their table, or shoes on their children’s feet. For these people, any price other than free entry is too high.

Stringing flowers sold at 10 Rs a strand? Spending 15 Rs on a ticket is probably the last thing on her mind.

Even free entry wouldn’t necessarily persuade them to visit a sight, considering the hidden costs of visiting. To start, there’s transportation, food, and accommodation.There’s also the opportunity cost of time. Time spent sightseeing is time not spent making money to feed the family.

People are, and will always be, priced out.

This truth isn’t confined to the third world, either. Not all Frenchmen can afford to visit the Louvre. The same goes for Americans and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This is a sad truth, but it’s the truth.

Conversely, people visiting sights in the third world usually have disposable income. And in these countries, if you have disposable income, you usually have a lot of disposable income. Another sad truth.

For the upper and middle class in these countries, a small increase on an already trivial ticket price will hardly hurt their wallet. They’re also walking proof that the argument of foreign tourists always having more money is far from true.

Not convinced about poor locals? Head to Qa’leh Rudkhan near Rasht, Iran to rub shoulders—and bump DSLRs—with local tourists.

It hurts the local economy

One of the responsibilities of sustainable tourism is to ensure your tourist money goes into the local economy. Dual pricing systems, unfortunately, have an adverse effect.

If I spend 500 Rs to enter a sight in India, that’s 500 Rs not spent eating or drinking at local restaurants. If I spend 200 Rs to see a museum, that’s 200 Rs I can’t spend on a rickshaw ride.

In short, the more money I spend on sights, the less I have to spend on the local economy.

Some would argue spending the money on the sight is helping the economy. But considering most sights are run by governments, and these governments are notorious for pocketing (and wasting) money, you have to wonder if the money will ever make it back to local economies. I daresay it won’t.

You’re much better off buying a cool lime juice (or three) from this lovely lady than spending the money on a government-run sight.

In my opinion, having a fair rate across the board for both locals and foreign visitors is not only equitable, it’s economically prudent. In the case of independent tourists, money not spent on sights is much more likely to end up in the local economy, in the hands of people that need the money much more than some fat-cat official in his lofty mansion.

At face value, dual pricing might seem like a good idea, maybe even a honorable idea, but look a bit harder and you’ll see why dual pricing is unfair, unjustifiable, and unwise.

The Sheikh Lotfallah mosque in Esfahan, Iran, another stunning sight with wildly discriminatory prices.

The price of foreign sights is irrelevant

Dual pricing is often justified by officials pointing out the ticket price is still less than they are in other countries. This argument is the most nonsensical of all.

True, ticket prices for cultural sights and museums are much higher in Western countries than they are in most Asian countries. But so is food. And accommodation. And public transport.

By this reasoning, everything should be made more expensive to foreign visitors because hey, it’s still cheaper than it is back at home! Taking the metro in New York City costs $2.75, so should the metro in Tehran be 90,000 rials a ride? A sandwich in London can go for £8, so should a dosa cost 675 rupees in Hyderabad? I think not.

A dosa for 60 rupees… as it should be.

Purveyors of this argument forget that the cost of living, space, upkeep, and wages are much higher in Western countries. Given the cost of living, a €25 museum ticket in the heart of Amsterdam makes sense. But this does not justify a €10 museum ticket in a country such as Pakistan or Indonesia, where all costs are much, much lower. The two are unrelated.

Lahore Fort in Pakistan is beautiful… but the price discrimination is insane. Foreigners: 500 Rs. Locals: 20 Rs.

Many tourists flock to Asian countries precisely because they’re more affordable than the West. By embracing dual pricing, and by inflating tourist ticket prices to rival their western counterparts, officials destroy the allure of visiting their country. Upset tourists, offended by price discrimination, will avoid the country and its sights in the future, hurting its economy in the long run.

The solution?

Who am I to criticize if I don’t offer a solution?

The solution, to me, seems simple: a uniform price across the board, with special arrangements for students, children, and the elderly. The price point would ideally be somewhere above the current local price, and below the current foreigner price. In many cases, locals prices completely exonerate locals from responsibility for the sight. It is cheaper to enter most sights than it is to get there by public transport.

A uniform price isn’t just fairer, it’s beneficial to the local populations, it shifts more responsibility towards the local population, and such a move might force officials to make better use of the income they do generate.

The next—and more difficult—step? Convincing governments to listen.

Still feeling the financial injustice? Here’s more to stoke the fires: I’m foreign, so I must be rich.

Yes! i support your argument. It’s a bitter reality that sometimes foreign tourist are seen as ATM machines. It should be understood that everyone on this planet has emotions and feelings. These type of problems generate bad feelings and ultimately damage the image of a country.

In the long term that’s definitely one of the problems. Unfair practices can hurt the appeal of a country drastically.

I second you on this one! I have faced it everywhere in Southeast Asia! Got my first shock in Grand Palace, Thailand and hence i did not visit it!

In Thailand, the price differs even for the water parks! That is complete nonsense and extremely annoying! Most of the people traveling save their asses off (at least I do) and I don’t do it to pay a triple to 4X to 90X the price locals pay!

Yeah. It seems these policies are made with a certain type of tourist in mind, and don’t take into account the diversity among tourists.

Although I understand that it’s not nice to pay so much more as a foreigner, I would still say that it makes sense. Maybe not 90 times as much, as in Petra, but there should at least be some difference between those who pay for the upkeep of a monument through taxes and those who don’t. For example, I need to pay 20 euros to visit our national museum and so does every foreigner, whereas the national museum is partly kept up with the tax money I pay. How is that fair?

A valid point. Though I think less of your taxes are actually used for the upkeep of cultural sights than one might think, a slight difference in local/non local price is palatable for that reason.

… but, on the other hand, that same argument can be used for sights in developing countries receiving funding from international organizations, which are also supported by money from taxpayers. If an American visits a park funded by US AID in another country, for example… what then?

It’s a tricky subject!

You make some great points! I’m travelling to Southeast Asia on a very tight budget soon and it’s annoying that I’ll likely be paying many times what the attraction is worse compared to locals who will be getting the ‘fair’ prices. I do agree with Brigitte below though that where locals will have already paid through taxes for upkeep of national monuments, the dual pricing seems a bit more fair.

On the bright side, many sights in South East Asia are at least somewhat well organized 😛 Many of the countries are still corrupt, but at least they have toilets at the sights 😉 It will be interesting to see if you agree with this by the end of your trip.

This is such an interesting argument. I always just paid it assuming it was my “tourist tax” and thats how things are. But you’re point about how the money spent on the inflated enterance fee is going towards corruption and not towards to local economy really made me think.

Glad you’re thinking… that’s the point! Of course, it’s (hopefully) not always the case, so it doesn’t hurt to assess where your money is going when you visit places.

Ask yourself: does the foreigner price seem reasonable price based on the costs of other activities in the country? How about the local price? Are the facilities well maintained if the sight is expensive? Is the sight in decent condition, or being actively repaired?

Being complacent with the way things are never got humans anywhere 😉

This is a very interesting topic! I’ve always thought that it’s OK that tourists pay more than the locals, but it’s a very valid point that the money would be better spent in the local community. This has definitely changed my perspective on it.

I think that’s the most compelling argument at the end of the day. Especially for wildly expensive sights like Petra, that’s a large amount of money that could’ve been put to much better use by locals. When that money goes to the government, even if it is used responsibly, the effects will take a long time to trickle down to the common man.

Hi Sebastiaan,

Neat post 🙂

I chalk this pricing deal between locals and tourists as one aspect of traveling. Some countries take a poverty conscious, scarcity approach to pricing stuff at tourist spots, assuming tourists have more money than locals or they should pay more because they are guests. I just pay and think little about it, only because it is….what it is 😉 Also, I feel it is such a blessing to be able to see these places that I’ll pay the Foreigner Premium LOL.

Thanks for sharing.

Ryan

Glad that you like it.

That’s one of the reasons I wrote the post: to challenge the status quo way of thinking. I do know what you mean with feeling blessed though, and plenty of places are worth the money. I just don’t agree with the thinking and logic behind vastly different prices between locals and foreigners.

You’ve raised some points worth considering, but haven’t swayed me entirely to your way of thinking.

Even you call it “an already trivial ticket price”, so why not give the operators the benefit of the doubt? And give the locals a slight sense of patriotic entitlement, of pride in knowing they’re able to get “a deal” that outsiders aren’t entitled to. You assume you know what’s happening with the money, but you don’t know all the goings on either. I’m not disagreeing that some (or most) of that money is pocketed by unscrupulous people – but it is ultimately spent and contributing to the local economy. Just not by you.

But you’ve definitely got me thinking about this issue – which is common in Turkey, where I live as an expat – in a new light. So thank you!

I respect your considerations, and agree to an extent. A situation where the foreigner price is double that of a local, or where residence of the area where the sight is situation go in for a discount or for free, seems like a perfectly acceptable middle ground. With the way most pricing is set up now, though, it seems that locals are totally exonerated from any financial responsibility for their own heritage, which seems strange.

I don’t agree with the idea that pocketed money flows back in the economy. It much more likely to flow to some Swiss bank account, or being spend on lavish dinners at expensive restaurants. Hardly places that need it most.

I know I don’t have a clue what actually happens to the money charged, and that is exactly one of the problems: no transparency and no accountability.

I’m glad I got you thinking about it, though, and your comment has done the same to me. Thanks for that!

Tiny Gemiler Island, a 1 km x 400 m island near the town of Fethiye, Turkey is an environmentally protected area that houses the ruins of 4 churches built between the 4th and 6th centuries to honour St. Nicholas of Myra. Last year, entrance to the island was 5TL for nationals, 7TL for foreigners. (Lots of people bypass the entrance fee by accessing the island by “alternative entrance points”.) I’m pretty sure the guy that rows his little boat over to the island every morning to collect fees from visitors doesn’t have a Swiss bank account. The thought made me smile though 🙂

I understand what you’re saying – championing transparency and accountability is laudable. I’m just having difficulty seeing this particular issue as black / white. There are so many shades of grey in the world.

But on the other hand you have all the paid sights in Iran, Pakistan, India, Jordan, etc., that charge a hefty foreigner premium without ever really justifying where the money goes. Corruption is basically institutionalized in such places, and I have a hard time believing all the money collected somehow flows back into the local economy. Or in the national economy, for that matter. See for instance the discrepancy in the Taj Mahal numbers I mention in the article. That’s a heft sum of money.

Ans sure, there will always be places where my arguments don’t hold true, for which I am happy, since that means that the money is well used. But that doesn’t mean that we should turn a blind eye and take it as it is at places where this isn’t the case.

Great set of arguments you have there! Another item I might add is how certain attractions charge in USD instead of the local currency and this really disadvantages travelers from other developing countries with weaker currencies.

We never understood why sights do that. I guess it’s to fight the possible effects of inflation on the local currency. But you’re right, the moments you’re not from. Europe or the States, that’s adds an extra layer of costs to the equation.