Part I of my most terrifying travel experience to date: that time I accidentally almost died in a remote village in Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains.

Nearly dying has a funny way of ruining travel plans.

Originally, I had grand plans to roam Tajikistan’s oft-visited but rarely written about Eastern Pamir region. Day hiking around Murghab! Yurt stays at Rang Kul Lake! Trekking through the Pshart Valley! Living local in Shaimak village! The finale: hitchhiking over the Qolma Pass between Tajikistan and China to get to my first ever women-only tour of Pakistan.

… but instead of hiking up mountain passes, I ended up in a middle of nowhere hospital, hooked up to an oxygen machine, with needles sticking into my bum to stop my brain from swelling to the point that I went comatose or died.

Shit happens.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let me take you back to where it started, some time ago in a valley far, far away….

Shaimak village from a 4,600m mountain pass

Something fishy

On my fourth evening in Shaimak—yes, I did at least make it to Shaimak—I was beat.

Rather than packing my bags for the next day’s 6 AM taxi to town (the last for two days), I sprawled on the floor. After hiking 25 mountainous kilometers at more than 4,000 meters above sea level, I was running on empty. Lazily eyeing my entropic pile of clothes, I decided to wait a couple more days to leave.

In retrospect: I chose poorly.

That night, fever settled in. Or, rather, shot me out of the sky and pinned me to the floor. Chills rattled my body as I weakly wrapped myself in every fabric within arm’s reach… all to soon be shed again when my body began burning feverishly. Sweat, repeat.

For a brief moment the next morning, I thought I still resembled a living creature. That notion quickly dissipated when I attempted to do my laundry and ended up too dizzy to stand, let alone scrub underwear in a fishpond (or contemplate the consequences of washing clothes where you raise fish for food).

Appa and a neighbor washing sheets in the pond

I wobbled unsteadily past my homestay host, affectionately referred to everyone as appa, mother, as she prepared breakfast.

“Alexandra! Как дела?” How are you? she asked in Russian, our only language of communication.

My head hurts… my stomach hurts…. everything hurts, I mumbled.

Her brow furrowed in concern, but I was already in motion. I returned to my room and collapsed onto my floor cushions, not realizing at the time how familiar I was to become with them.

Sheepish odors and butt Benadryl

For two days, I swam in and out of hazy consciousness while drowning in sweat. Wrapped like a steaming manto in all the blankets I could find, my hands rarely emerged except to sip tea or tap to the next page on my Kindle.

As I devoured the entire Golden Compass trilogy, pondering daemons (mine would be a flu-ridden ferret) and magic knives slicing pathways to parallel universes (I would cut to a universe with Netflix), Appa played overenthusiastic bed nurse.

Golden in both heart and teeth, she brought me food every few hours. Each time, she insisted the current dish was best for flu: piping hot bowls of mutton and potato soup, steaming plates of mutton and rice, cold boiled mutton with bread and yogurt, plain noodles topped with—you guessed it!—mutton.

Appa cooking what she does best: mutton

I nibbled each halfheartedly as she watched attentively, silently cursing whatever god or genetic mutation brought sheep and their flesh into existence and into my bowl. My room reeked of filth, sweat, and mutton; the odor hit me every time I returned from a perilously unstable trip to the drop toilet outside.

Appa’s overzealousness didn’t end there. She regularly dosed me with aspirin, Russian paracetamol, and her favorite “Aga Khanskii paracetamol”: white tablets distributed in little plastic bags by the Aga Khan Foundation. Better than Russian paracetamol! Not expired! 500 milligrams! she insisted.

Despite her mutton and medication regiment, my fever persisted. Concerned about my 39.4°C (102.9°F) temperature, she called her daughter-in-law-cum-doctor. The woman arrived clutching a small white box in her hand.

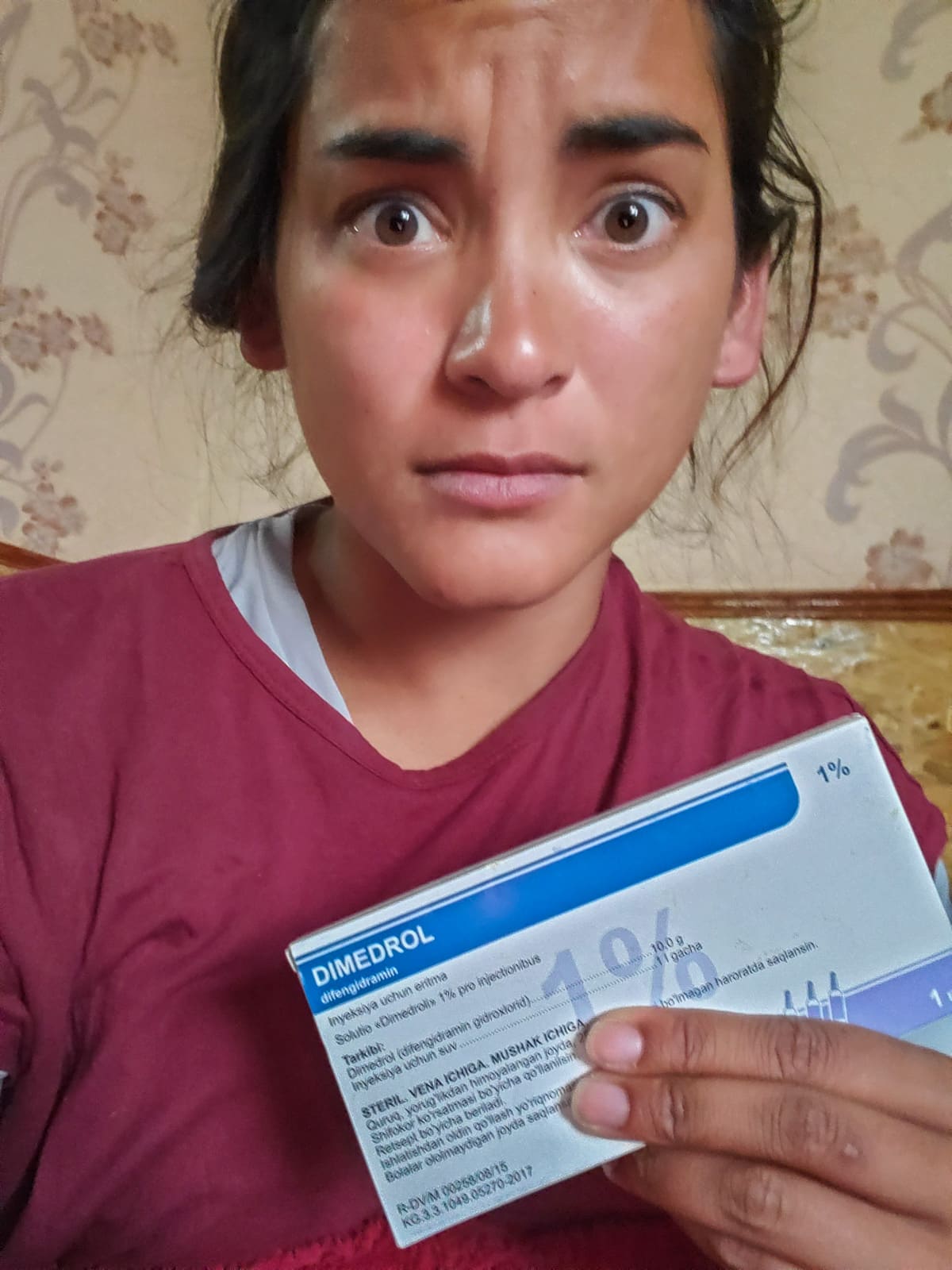

Together, they implored me to try something else: a medicine, “ukol”, that would make me much better. I examined the white box—“Demedrol”—but the explanations were in Russian and Turkish. My Russian vocabulary didn’t include ukol; I stared blankly at them. Appa wiggled her eyebrows suggestively in response, rotating her hips to mime something stabbing into her bum.

Oh, that’s ukol.

Panicked at the idea of a random village woman giving me an anal injection in a place without running water or gloves, I feverishly employed all the Russian I could muster to ramble about how excellent the Aga Khan medicine was and how I certainly didn’t need anything else and please could I just have more aspirin and paracetamol please?

The women were dubious, but sympathetic. I made a deal with Appa: if I took the paracetamol and my temperature did not go down, they could inject me with whatever was in the Russian/Turkish box. As they left the room post-dosage, Appa gave me a stern look to let me know she was serious about our deal.

Immediately, I flung all the blankets off my body in an attempt to lower my temperature, and grabbed my phone to Google Demedrol. 5 minutes later (signal is bad in Shaimak), I learned Demedrol is simple allergy medicine, more commonly known as Benadryl in the United States. The women want to shoot Benadryl into my butt. Groaning, I collapsed onto my pillow.

I should’ve gotten that taxi.

Obligatory “oh shit I just figured out they want to shoot Benadryl into my butt” selfie

On the third day, walk to the East

On the third day of flu, I thought things were finally improving.

My head hurt a bit less. Walking didn’t make me feel like passing out. I was almost hungry (for anything but mutton).

Most of my day was spent in bed, but my first lunch at the kitchen table in days—only potatoes, thank the mutton gods—made me bold. Ever stubborn (and stupid), I reasoned if I could survive sitting at a table, I was probably fit enough to go for a walk. I’d been bedridden for days; it was time to get some fresh air!

Around sunset, I climbed to a cave up the mountain behind my homestay. “Climbing” is a term used loosely—it was more like walking three steps, telling myself I was not having a heart attack, then continuing on after heaving for minutes.

Puffing, I reached the cave, read for a bit, and ate an apple I’d stashed away for emergencies. Despite climbing’s strain, it seemed harmless. Words, fresh air, fresh fruit; what could go wrong?

The answer: that night, everything.

At least the view was worth it. I think.

In which my head explodes

Come evening, after watching Appa’s daughter Nilu show off some Bollywood dance moves for an hour, I tucked in early, hoping to sleep long and well.

Sleep never came; the most splitting headache of my life did.

Around 10 at night, searing pain blossomed from my temples, creeping around my head until it felt like it was engulfed in flame. I tossed and turned in agony. With every turn my brain sloshed, pressing against the walls of my skull, trying to burst free. Breathing was impossible; I felt like I was asphyxiating.

All night I cried and gasped in pain, clutching my head, praying to a god I don’t believe in that someone would come to help. I had no medicine—save the box of butt Benadryl—nor energy to find some. It was one of the longest nights of my life.

After hours of agony, gray light began filtering through the window. I heard someone in the hallway. It had to be Nilu getting up to milk the cows. She could get me medicine!

“…. Nilu….” I moaned. No response.

“Nilu…. help… pomogi minye… Nilufar…” The louder I called, the more my head split. I couldn’t handle my own voice. Footsteps shuffled away to the kitchen; I cried. I strained to reach the wall next to me, but couldn’t; the effort left me breathless. I grabbed my water bottle and weakly tapped the wall, calling Nilu’s name. Please someone come. I need help, I’m not okay.

An hour passed; no one came. I couldn’t bear the pain any more. Unsteadily, I climbed to my feet, stumbling over nothing. I shuffled to the door as my vision distorted from pain.

Emerging zombie-like into the hallway, I saw Nilu’s silhouette in a doorway. “Nilu,” I croaked desperately in English, “I need help. My head. Lekarstva yest? Paracetamol?”

Nilu’s eyes widened at my appearance. Insisting I lie back down, she ran for her mother.

Appa quickly appeared, armed with packets of paracetamol. “ALEXANDRA, КАК ДЕЛА?” her voice boomed, and I couldn’t help but scream in pain. Her brow furrowed as I curled into fetal position. She could tell I was much, much worse than before.

She helped me sit up and take the medicine—three tablets of who knows which paracetamol—then lied me back down… and began sobbing.

WHEN YOU ARE SICK, MY HEART HURTS, she wailed in Russian, pounding her chest.

YOU ARE MY GUEST, I MUST TAKE CARE OF YOU, BUT I HAVE NOT. Tears began to flow from her crinkled eyes.

YOUR HEAD HURTS, AND SO MY HEART HURTS. When she sniffled, her gold teeth flashed.

Appa continued bellow teary variations for several more minutes; I was torn between feeling touched and passing out from pain.

Eventually, she ran out of platitudes. Wiping her eyes, she scuttled off to fetch more tea. I closed my eyes and tried again to sleep through the searing pain.

Goddess, gone

Hours later, I lay stretched on my floor cushion surrounded by bowls of rice, mutton soup, tea, dates, yogurt, melons, and apples that Appa brought me. Like temple offerings to a goddess in repose, except I reeked of stale sweat, mutton, and a week’s worth of filth, and was barely conscious enough to process any of it, let alone respond to would-be devotees in Russian.

If I never see mutton again, it will be too soon

Appa called a medic, a soft-spoken woman in a pale pink headscarf. She hovered over me, quietly checking my blood pressure and listening with a stethoscope as my homestay family observed my limp form over her shoulder. Appa kept up a running commentary of diagnoses and treatment suggestions at full volume, each comment from her gold-plated teeth making my head spin. I whispered for her to speak softly, but no one heard me.

Once it was ascertained that I was, in fact, not okay, the medic disappeared to call a doctor in Murghab, the nearest town… four hours away. Appa relayed the conversation slowly, deliberately, loudly.

SHE WILL BRING YOU TO MURGHAB. I squeezed my eyes shut in pain.

YOU CAN RENT A CAR. I curled into fetal position and clutched my head.

THERE IS HOSPITAL THERE, A DOCTOR. EVERYTHING WILL BE OKAY. I whimpered and nodded slightly, my head spinning.

I pondered staying one more day to wait for a shared taxi—US$70 for a private taxi was well out of my budget—but my head throbbed. Was town lower than Shaimak? I couldn’t remember. Maybe. Probably. Right?

I agreed to hire the taxi.

They pressed more pills on me. Paracetamol? Aspirin? I asked hopefully. No, these were better, they insisted. Russian explanations of their effects were beyond my comprehension (and, at that point, care). I choked them down.

The medic pulled out a familiar sight: a box of needles and butt Benadryl. Despite the pain, I pulled myself together enough to resist in Russian: No, please. Don’t need. They insisted it was for the car ride.

I patted blindly through blankets, pulling out my phone to open Google Translate. Blue light blinded me, sending new waves of pain through my head. I persisted and slowly typed: “I can’t take. Maybe bad. I have drug allergies to sulfa.” Women clustered around the phone, murmuring allergya, allergya. It seemed to deter them. Thank the mutton gods.

Gradually the crowd dispersed, some to help find a car, others bored. Appa unsuccessfully tried to help me pack my backpacks. Packing was physical agony: the best I could do was alternate between putting something in place, then lying down in exhaustion for several minutes before trying again. Half an hour later, there was order to my chaos.

The medic returned; the car had arrived. Appa’s strong arms bulged with muscle as she heaved my backpack shut and zipped it. One more pill was clutched in the medic’s hand. For the car ride, Appa explained, since you have allergies to ukol. It will make everything good. She made a cleansing motion with her hands. Seemed reasonable; I took the pill.

It was time to leave Shaimak.

A polished part of the road to Murghab

Wait, that’s not drugs

After weakly saying my goodbyes to the family, I crawled into the ancient blue jeep that brought me to Shaimak a week before. Medic woman climbed in behind me with two young children in tow. I eyed them warily in the rearview mirror; one scream and my head might pop.

Pulling my shit together to take a happy family selfie despite impending doom; now that is professional blogging

Eager to make an extra buck, the driver bumped around the village picking up packages for delivery en route. Suddenly, while idling outside a house/petrol shop, a new sensation hit me.

My body was melting.

Feeling drained from my arms, my legs, my face. I pressed my hands to my face to make sure it was still there, absolutely certain it would fall off if I didn’t. I tried to wiggle my limbs to ensure they still worked, but they responded sluggishly.

It was terrifying.

My fear amplified as the jeep’s engine roared to a start. We were beginning the four-hour dirt road drive back to Murghab.

The ride was the longest and most agonizing ride I have ever been on in my travels. Coming from a girl who’s endured multi-day escorted border crossings in Pakistan, a four-day journey in a Russian train, overnight journeys on the floor of Bangladeshi ferries, and 12+ hour rides in overstuffed Indian jeeps, that’s saying something.

Wretched Russian techno blasted from the driver’s portable speaker, “I LOVE YOU” and banal variants of the phrase forcibly assaulting my withering mind. Every bump felt like a knife stabbing my head, but I was too terrified about my melting body to fully process pain.

The medic’s children screamed (the Chekhov’s gun of public transport), the jeep bounced, and I dug through my bleary memory trying to recall the name of the medicine the woman gave me. Did it contain sulfa? Is this an allergic reaction? Some freaky Soviet opiate? What the hell am I ON?

Data signal returned as we raced closer to town. I Whatsapped my neuroscientist father in a confused panic, telling him I was in remote Tajikistan, drugged and melting and driving toward a hospital. He asked what medicine they gave me pre-drive; I relayed the question to the medic.

After asking verbally in Russian, then textually in Russian, Tajik, and finally Kyrgyz (thanks Google Translate), the medic finally understood my question. She hummed and hawed for literally twenty minutes before finally recalling her seemingly lethal dose: “Cardiamin”.

I relayed the name to my father. After a brief pause, he responded: cardiamin is a vitamin. The melting sensation? That wasn’t drugs; that was my brain.

Oh. Shit.

Murghab hospital

On my deathbed

As the realization that I was in slightly more danger than I thought began to sink in, the jeep finally rolled up to Murghab hospital.

I was barely conscious, desperate for oxygen. To speed up the process, I tried to get out of the car by myself and walk into the hospital… but my body and my brain were no longer connected. Instead of walking through the hospital entrance, I crashed into a wall.

The medic took my arm and steered me down a hallway to an empty room, where I collapsed onto a bedspread covered with clip art roses and “So Very Lovely” repeating in cursive across the fabric. Someone eventually brought my backpacks in—I hadn’t even realized I left them behind. At my request, a nurse brought me a cup of water from a bucket. It tasted strange, but finding my Steripen to sterilize water was too much effort; I drank it anyway. Deathbed logic: parasites couldn’t be any worse than the situation at hand.

Eventually, the doctor arrived: a mid-forties Kyrgyz man in a white baseball cap and dad sweater. He asked my name and where I was from in Russian, I responded weakly in the same tongue. Delighted that I could speak some Russian—despite mumbled insistence that my Russian was very poor—he continued on.

You are not feeling well? he asked.

No, I just rode in a techno!jeep from hell for four hours to hang out in this busted AF hospital for fun, I thought impatiently. What do you think?! I bit my tongue—good thing my Russian is too bad for douchey sarcasm.

No. My head hurts very badly, I responded, I need oxygen. I didn’t know how to say oxygen in Russian.

The doctor stared uncomprehendingly. I tried “oxygen” in a variety of American cinema-esque Russian accents without success. Defeated, I pulled out my phone, grimacing in pain from the glow as I translated: Мне нужна кислород. Closing my eyes, I showed him the screen.

Ah, oxygen! You want oxygen? We have oxygen.

PLEASE. I was too pained and panicked to worry about the fact that I needed to instruct a doctor to bring me oxygen. He exited the room, chuckling and wrapping his tongue around the word “oxygen”.

I lied back down on the bed to appreciate that, if I died, at least I was already on a bed of roses.

End Part I

Part II: terrifying toilets, breakfast bum jabs, and a deadly diagnosis.

Safety note on altitude sickness: Humor aside, I now understand this experience could have been fatal or caused lasting brain damage. Altitude sickness (AMS), especially advanced forms like HACE, are a serious risk when traveling the 3,000m+ Pamir Highway. You must be careful when traveling at high altitudes: avoid sleeping more than 1,000m higher than the previous night; stay hydrated and do not overexert yourself; pack AMS medications such as Diamox (if you’re not allergic to sulfa) and dexamethasone in the event of HACE. Most importantly, educate yourself on symptoms of different forms altitude sickness and treatment options should any occur.

I’m so glad you’re all right!

Yeah me too!

Absolutely love your spririt, your writing, and your blog! Please, keep it coming… Glad you’re doing better now, take it easy, take it sleazy!

Thanks for sharing your story – this is extremely important!! It has not been once nor twice I have met tourists at high altitude risking their lives without clearly understanding how serious AMS/HACE/HAPE can be. I have suffered for AMS myself and the experience helped me to understand how easy it’s not to take the symptoms seriously. The golden rule is: if you are not feeling well at high altitude, you should always treat it as AMS unless you are 100% sure it isn’t.

I just love to read blogposts about unexpected destinations 🙂 Loved your adventures here <3

Glad you’re all right…… You could keep a strip of acetazolamide with you in case of plans to venture into high Altitude again….. Thrice daily on the day prior to ascent and continued for the next three days should take care of it….. And be careful not to ascend more than 500 ft a day…… Cheers!

And @prat is right….. High Altitude is not joke!

I gave cbd gummies a prove with a view the maiden time, and I’m amazed! They tasted excessive and provided a sanity of calmness and relaxation. My emphasis melted away, and I slept well-advised too. These gummies are a game-changer for me, and I extremely commend them to anyone seeking appropriate emphasis relief and think twice sleep.

Glad you are alright and your sprit was good. Enjoy reading your blog and again you are a very funny girl. Great personality.

Great post.